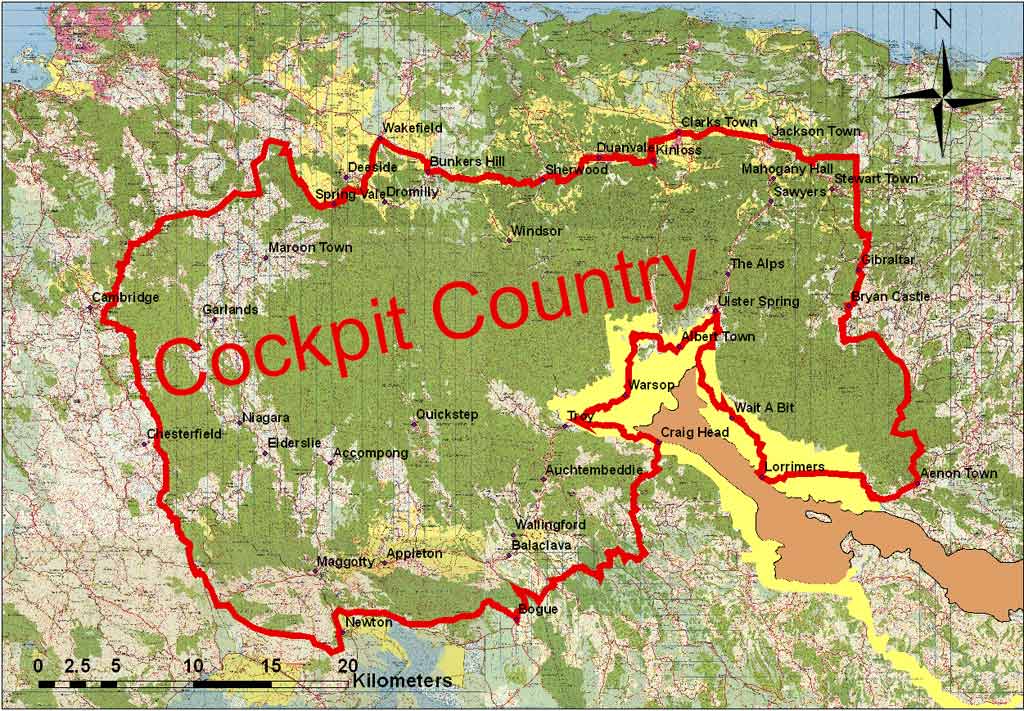

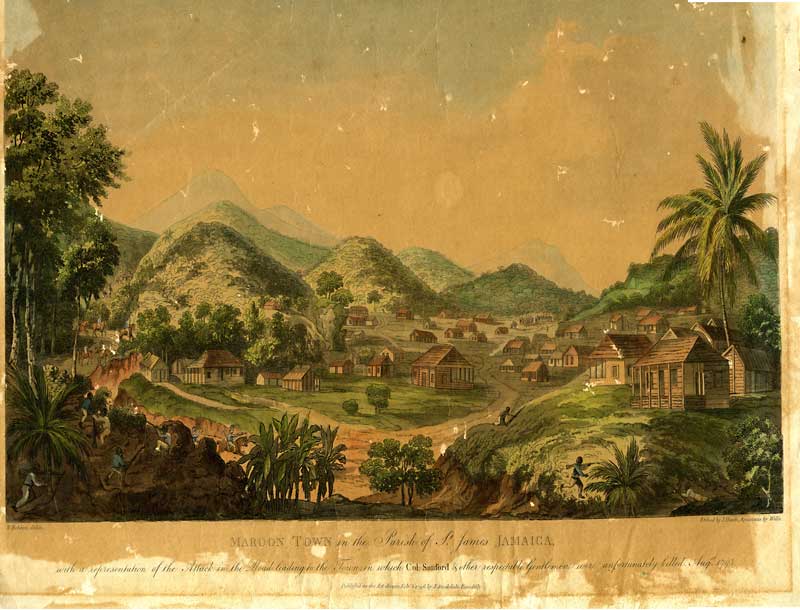

The history of the Trelawny Maroons is not merely a story of escape from slavery — it is a story of nation-building in the face of impossible odds. For over 80 years, they fought, survived, and built a free society deep in the mountains of Jamaica.

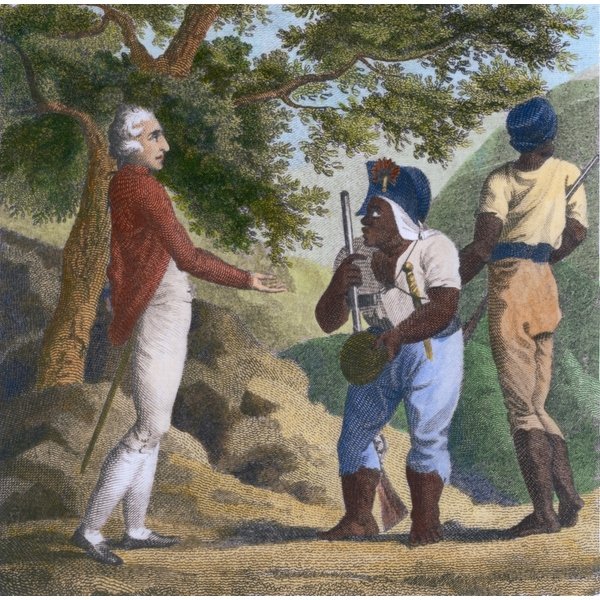

Born from the ashes of Spanish Jamaica, these descendants of enslaved Africans refused to accept bondage. They fled into the interior, forged communities in the mountains, and built a resistance movement that the British Empire could not crush. Their story is one of the most remarkable in the history of the Western Hemisphere.